In my first year teaching high school history, my classroom management was a disaster. I believed that the students would simply cooperate with a teacher who was cool and not mean. This belief proved to be unfounded. A veteran teacher told me that sometimes the solution is to give out detentions. So I did, with verve. I gave out more than I should have, and that simply killed the classroom culture. When I think about it, I find myself burying my face in my hands.

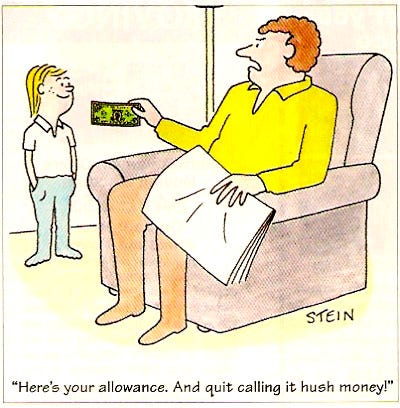

How does this anecdote connect with paying kids for chores? Because it’s about attempting to use intrinsic (internal) and extrinsic (external) motivation, both done badly.

“Do not pay for chores!” say many parenting advice-givers. This is the opinion of Ron Lieber in The Opposite of Spoiled, of Andrew Coppins and Lucía Alcalá’s study of traditional cultures’ approaches to parenting, among others.

Their reasoning is clear: if you’re motivated by rewards and punishments, then you’ll no longer be motivated by higher, better reasons: community, enjoyment, and the desire to do a good job. Extrinsic motivation crowds out intrinsic motivation. This is the Motivation Crowding Theory that we looked at in this post. It doesn’t just apply to payment, but to any kind of reward or punishment. Does extrinsic motivation really crowd out intrinsic motivation?

I knew just who to ask about this. I reached out to John Lightle, a friend and colleague at Virginia Commonwealth University, and piano player in his extremely talented family’s cover band. He is also a behavioral economist, which means he studies the shadowy psychological side of economics, in which people's motivations are mixed, mercurial, and sometimes contradictory.

Here’s what he told me about motivation research (I'm quoting him freely).

Incentives matter.

Paying people for tasks works, but it sets a standard to expect payment for work. For example, paying a kid to get good grades makes him care about the grade at that particular time, but it doesn't “train him” to work hard when he's not paid.

Many behavioral studies are specifically designed to show that incentives don't work the way you normally would think. These studies are narrow in scope and are a minority of real-life situations.

Rewards work best when they're based on the quantity and quality of work performed.

Extrinsic motivation is bad when people have intrinsic motivation to begin with. Don't pay them for things they do for fun (why would you need to anyway?).

If you decide to pay, pay enough, or don't pay at all. Small financial incentives can backfire, while larger ones work.

Studies that tell parents and teachers not to use extrinsic motivation are usually looking at situations where the task might be at least a little bit interesting or new. But there are some familiar tasks that everyone hates. Do you like to pull weeds or fold laundry? No one does. Why should we expect kids to want to do boring tasks?

Remember my post from two weeks ago, when I was trying to get my seven-year-old to pick weeds? He very much did not want to do that. I had gone through reminders to boost the relevance, belonging, and growth mindset for his tasks, but ultimately it was the promise of reward (getting paid) and threat of punishment (not being allowed to bounce on the trampoline) that made him actually do the work.

Here's some principles that come out of all of this:

Foster intrinsic motivation whenever you can. Resort to extrinsic motivation when you must.

If the work is important, done in connection with the rest of the family, and the kids feel they are growing toward something, that will help. Target relevance, belonging, and growth mindset.

You need clear goals and expectations for chores. If you don't have these, nothing will work.

Make sure you don't make new expectations that interfere with old ones.

Carrots and sticks will make sense to the kids - and therefore be more effective - if they understand the structure and goals you're both working toward.

Punishments should be predictable, understandable, and proportional to the offense. Kids should know what's coming if they break a rule. Surprise punishments are just parents pulling a power trip.

If I had known these as a new teacher, I would have been better prepared to reach my students.

I've talked to several sets of parents about whether they pay for chores. I’ve found that they often use the following two-tier system: most chores are because “you have to” and aren't paid (especially cleaning up after oneself). “Extra” jobs are paid. I think their instincts are correct here. The “you have to” jobs fit the expectations they've built in their households over time. The extra jobs add motivation and help teach about money.

Payment for chores is a weak motivator. But it's good for teaching the connection between work and money. We'll discuss that in future editions of Paper Robots.

This series on motivation has been tough to write. I had to learn a lot of new things. Maybe it was tough because there are no clear-cut rules. Parents (and teachers) need to use wisdom to find the right balance between rewards, punishments, guidance, and encouragement.

Stephen, I enjoyed reading your finished post (we met at a wine bar where your college roommate was playing music in Charleston last Saturday).

I might add a small tip from my work: teaching kids (and adults for that matter) Gratitude can also be appropriate and effective. Instead of "you've got to" do this or that task, change the "o" to an "e". Thus, "you get to" do something. What I'm suggesting is that there are people in other circumstances who would trade places with you and your kids in a heartbeat. They may be living in poverty, under conditions of war or tyranny, be the victims of natural disasters, and numerous other circumstances not of their choosing. We get to do boring, uninteresting things in order to maintain and sustain our privileged lives. We get to live this way because of the blessings we have. It's something to appreciate and not take for granted.

Great article.

One every parent can relate to.

Good job.