Announcement: The Paper Robots family is going on summer vacation. The blog will resume on September 10.

Grocery shopping with kids can be a drag, according to exclusive reporting by me. You can read about this in my post on how to get your kids to stop bugging you to buy stuff. The kids are bored and surrounded by hundreds of things they want to buy. But there are constructive and fun ways to occupy elementary-age kids’ attention at the store. Each store product has clues that can give us a small peek into the lives of people all around the world. One clue that is attached to every product is the price.

I wrote about this in a chapter for a book for teachers. The book is Inquiry-based Global Learning in the K-12 Classroom, edited by Brad Maguth and Gloria Wu. Here’s what I wrote:

“Store prices have stories behind them. While many people just see price as a number (e.g., $5), that number contains a deeper story about a choice made by both a buyer and a seller. When a buyer purchases something from a seller at a certain price, it sends a little signal to all the other buyers and sellers in the global economy. A price does not tell a story all by itself, but it does offer a clue about its origins. Why, for example, is coffee from Jamaica more expensive than coffee with no origin listed on the package? How can we find where the coffee is from and discover the identity of the people who grew it? The mystery of the price invites us to speculate and to investigate.”

Below are other questions that kids can investigate at the store. (These are for kids who can read. For four- and five-year olds, have them compare large prices to small products and vice versa, and organize items in the cart. See here for a video example. Ignore the store’s prohibitions on children riding in carts—worst rule ever.)

For children to investigate:

Where is each product from?

Find a heavy product and a light product that cost about the same. Why may the light product be so expensive and the heavy one so cheap? (See an example of my kids doing this here).

Should we use the price or the unit price for the items we buy?

Which tends to cost more, products with lots of ingredients or just a few?

Which section in the store has the most expensive stuff?

Which costs more, healthy food or cheap food? Why do you think this is?

Asking questions like this raises kids’ awareness of the world around them–literally the world, since the products we buy come from all around the world. This helps them think about how humans are interconnected through the global economy. It helps them think about the cost of the things we buy. And it connects their awareness of the world economy to the family’s personal finances. When mom says “we can’t buy that; we can’t afford it,” the answer becomes a bit more meaningful to the kids.

Let’s go back to the case of the Jamaican coffee. What can it teach us about the world? From the Global Learning book:

“The coffee with packaging describing its origin is more expensive than the coffee that does not, which is labeled with vague terms such as ‘Lakeshore’ and ‘Daybreak.’ Why? Do the [children] think that the difference in price has more to do with coffee producers in Jamaica (supply) or with consumers in the United States (demand)? In this case, both answers are probably correct: It is more difficult to supply coffee if it must be carefully chosen and shipped from a single location, rather than if the coffee is thrown together from multiple origins. The single source coffee is also more scarce. But the idea of a single origin probably also appeals to upscale consumers who demand their coffee to be more exotic. This would be important information for entrepreneurs to know as they design products to sell.”

To be clear: You usually won’t know the reasons why the prices are what they are. But speculating is fair game.

If you manage to make it home from the store with your sanity and wallet intact and you still want to talk about money, here’s an activity. Show your kids the Numbeo.com price comparison tool. In it, you’ll type the name of your home town and some other place in the world. It will generate a list of products, comparing the prices in both cities. Some of the prices will be dramatically different. For example, the price to rent an apartment is 50% higher in Singapore than in Richmond, Virginia. Why might this be? Singapore is more crowded. But surprisingly, rental prices in Tokyo, Japan (another crowded place) are lower than in Richmond.

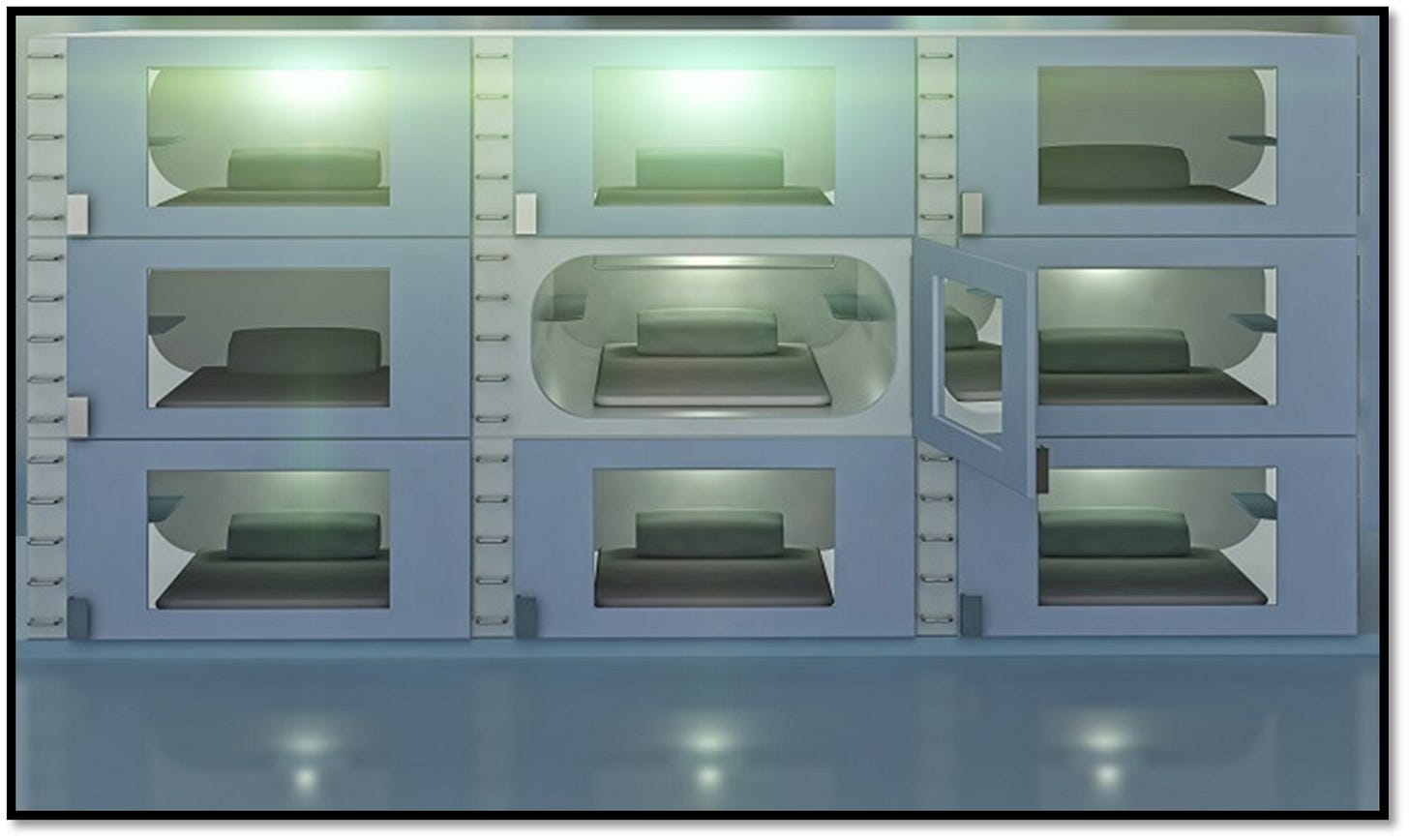

Of course, what you get for your rent payment in Tokyo is likely quite different from what you get in Richmond. For example, here’s a picture of one of Tokyo’s famous capsule hotels. Japan has had to be clever managing their limited space and large urban population. The relatively low rent in Tokyo shows that they’ve been somewhat successful (incomes are lower in Japan also; that probably has an effect on demand).

When you allow summer screen time, you probably haven’t had your kids pore over pricing data on Numbeo. It might not hold their attention like “American Ninja Warrior” or “Is It Cake?”. But with just a few well-placed questions at the store and a few minutes wondering with them about price comparison, your kids can get a better understanding of the world, its people, their place in it, and the value of a dollar.

Advanced students might be more intrigued by the difference between a cool G-Shock and a venerable Patek Philippe

Love this idea!